Too much information! Collection information at the National Gallery – Rupert Shepherd (April 2017)

In 2016, the National Gallery mounted a major exhibition, Painters’s Paintings, which took ‘its inspiration from works in the National Gallery Collection once owned by painters’. Yet, although we have used a digital collections management system since the early 1990s, the information that we needed to assemble the exhibition – who previously owned our paintings – did not exist in our database.

This may seem surprising, given the size of our collection: we currently have only 2,363 objects, a small number compared with most other museums. But many museums have similar problems with their digital documentation, and in the Gallery’s case, there are very good reasons for them.

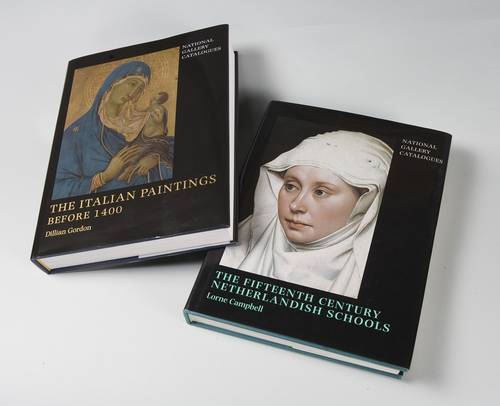

Two of the National Gallery’s most recent series of scholarly catalogues – Photo: © The National Gallery London.

Speaking on national TV in January 2016, our Director, Gabriele Finaldi, said that ‘the Gallery has probably more knowledge about its own collection than any other museum in the world’. The first printed catalogue of our paintings appeared in 1824, the year of our foundation; we published our renowned series of scholarly catalogues arranged by artistic school from 1945 to 1991; and we began an entirely new series in 1998. The most recent volume, Nicholas Penny and Giorgia Mancini’s catalogue of the 16th-century Ferrarese and Bolognese paintings, describes just 44 paintings in its 535 pages.

Several volumes of the National Gallery Technical Bulletin – Photo: © The National Gallery London.

And we must add to these the 36 volumes (so far) of the National Gallery Technical Bulletin; our many handwritten and typescript records (we have recorded cleaning and treatments systematically since 1855); analogue and digital photographs; digital information that has not yet found its way into our database; and digital systems like our MicroGallery [PDF], at the cutting edge when it opened in 1991.

The MicroGallery in the newly-opened Sainsbury Wing – Photo: © The National Gallery London.

But these notable achievements have also led to problems: faced with this much rich, detailed, narrative information and the highly structured space available in a collections management system (we use Gallery Systems’ TMS), we took the entirely reasonable decision not to try and shoehorn our information into the database. Instead, we made sure that the core ‘tombstone’ information which can identify the paintings was recorded in TMS, and then concentrated on using the system to manage painting movements, loans, and exhibitions. As a result, our database lacks information such as provenances, bibliographies, and structured links to places, materials, and techniques.

But the world changes, and in 2017 we find ourselves with a problem: an ever-growing online audience using multiple channels, very limited structured digital information that could be used to meet their needs, and no centralised system for storing data and texts and delivering them to those different channels so that we can develop rich, innovative ways of presenting our collection digitally.

Over the last year-and-a-half, we have been planning the solution. A generous grant from a charitable trust will fund a three-year Collection Information Project (‘CIP’) to greatly enrich the digital collection information that we hold, so that we can make our extensive knowledge and expertise about the paintings accessible to everyone.

After some initial enabling work, the project will fall into two parts. One will prepare our collections information for re-use, bringing together, connecting, structuring, enhancing and expanding our data. We will automatically extract structured data from a series of Word files which provide core object information and from the texts of our scholarly catalogues; catalogue books into our Library database so that we can connect paintings’ TMS records with books’ library records; and enter by hand any additional information which cannot be assembled automatically.

In the second part, authors and editors will produce a new short and long description for each of our paintings. We will also write longer essays on our 100 most significant works, and produce online resources which discuss materials and techniques, paintings’ functions, and the history of collecting and display. We will also review and update existing texts describing artists, styles, movements, media, techniques, subjects, and so on. We aim to produce content that can be reused multiple times in different contexts, without having to be rewritten every time, and so we also hope to make our data publicly available using established standards such as LIDO and the CIDOC-CRM (both of which were developed by CIDOC working groups), so that people can incorporate it into their own systems.

To enable the CIP to achieve these goals, we plan to commission middleware to link together systems including TMS and our library, archive, and image databases so that they deliver data together as a seamless whole. All this will feed into a new website, which will deliver much richer, and more inter-connected, information about our paintings.

But these are just first steps. We have much more information than we can deal with even in the CIP, and we must plan an ongoing programme to digitise and publish it. Our aim is to tell the stories of our objects from their creation to the present day using structured data. The middleware will let us make our information available to any consuming system, and we hope to take advantage of this to deliver it in other systems beyond the website.

The end result will be a step change in the richness and breadth of information that the Gallery holds digitally and delivers to its audiences. Having started with too much information to enter easily into our database, we want to give our users all the digital information they will need to understand and appreciate some of the world’s greatest works of art.

Visitors looking at three of the National Gallery’s Titians – Photo: © The National Gallery London.

Bio: Rupert Shepherd initially trained as an art historian, specialising in the Italian Renaissance, before moving into museum documentation, dabbling in humanities computing and digitisation along the way. Having managed the Ashmolean Museum’s documentation for three years, and the Horniman Museum and Gardens‘ for six, he has been Collection Information Manager at the National Gallery, London, since 2016. Rupert tweets at @rgs1510.