That’s mine too! – Maria Vlachou (September 2017)

Eden Condoms, Esther Pi & Timo Waag, Spain. Shortlisted for the 2017 Rijksstudio

Awards (source: Rijksmuseum website)

In his essay Culture and Class (2010), John Holden, the freelance writer, speaker, and cultural commentator who is also visiting professor of cultural policy and management at City University, London, talks about Culture’s guardians, namely cultural snobs (a small but still influential group, typified not only by its allegiance to certain art formsand periods, but by the insistence that only the already educated should enjoy them) and neo-mandarins (cultural enthusiasts who wish to share their enthusiasms with others, seeing everyone as capable of understanding and enjoying culture and keen to educate them in ‘high’ culture). Although there is a clear difference in mentality between the two, there is something they have in common: the need to maintain control.

In many countries – perhaps most countries -, there is continuing talk about “democratising” culture and creating access for all. Should we have a better look at this process of democratisation, we would easily realise that it isn’t democratic: culture’s guardians decide which culture is worth being created and having access to.

Digital technology, the Internet and social media have put a strain on Culture’s guardians. One of the most debated issues has been that of open access to collections, that is, the free, immediate, online availability of high resolution images of museum objects, as well as the unrestricted use, at no cost, of images of objects in the public domain – which means that these images belong to everyone and that the museum that holds them in trust does not have the right to condition their use.

Panel debate at Sharing is Caring 2015, dealing with Creative Commons for contemporary art. Photo: Jonas Smith on Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

In her forward to Sharing is Caring (2014), Merete Sanderhoff, Curator and Senior Advisor of Digital Museum Practice at the National Gallery of Denmark, reminds us that “The Age of Enlightenment fostered dreams of a united humanity, building on knowledge, education, and equal access to participating in society and culture. With digital technologies, we have stepped closer to fulfilling that dream. (…) Enlightened ideas remain at the core of the cultural heritage sector today.”

Fine, a noble cause. But does this mean people should be allowed to make birthday cakes, sneakers, condoms or toilet paper using images from museum collections? Who will protect the dignity of the objects from the assault of the masses? And how about the income museums are losing by not charging for the images?

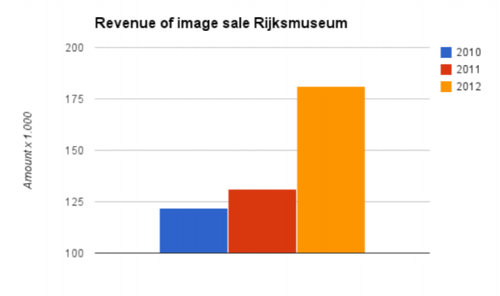

Starting from this last point, in Democratising the Rijksmuseum (2014), Joris Pekel, Community Coordinator Cultural Heritage at the Europeana Foundation, shares information about the evaluation of the Rijksmuseum’s open access policy. In 2010, when the museum had nothing available under open conditions, there was less revenue than in 2011, when the first set of images was made available, and in 2012 there was an even more substantial increase in image sales. Thus, this trail blazing museum disproved the common belief that open access policy has a negative impact on museum income. More museums followed suit: the National Gallery of Denmark, the J. Paul Getty Museum, the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., the Smithsonian Institution, among others, and, more recently, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which made available more than 370,000 images of public-domain works. This is not an issue just for big museums, though. Medium and small size museums have also seen the benefits of an open access policy, such as the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, MD, the Davison Art Center at Wesleyan University, and in 2011 the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, CT, that has made available about 70,000 images, even for commercial use.

Rijksmuseum’s revenue from image sales 2010-2012, Joris Pekel’s “Democratising the Rijksmuseum” report (p.12)

Thus, the next big question is: how do we know what people are going to do with these freely accessible images? This is, perhaps, the hardest thing for some museum professionals, who feel they have a responsibility to “protect” the works of art and their reproductions. The hard, truth, though, is that they do not. Objects in the public domain belong to everyone and no one has appointed museum professionals as arbiters of taste.

What made the Rijksmuseum move towards open access, in the first place, was the fact that a number of bad quality images were already circulating on the Internet and being used in all sorts of ways which did not benefit the museum. Thus, it took a realistic step, acknowledging the true impact of the Internet and digital technologies and taking control of this process by making available high-quality images from its collection. The notorious statement by Taco Dibbits, Rijksmuseum Director of Collections, back in 2013, still echoes: “If they want to have a Vermeer on their toilet paper, I´d rather have a very high-quality of Vermeer on toilet paper than a very bad reproduction”. In his report, Joris Pekel stated that “What greatly benefitted the museum is that other people started making new creative works with the material and therefore promoting the museum on a larger scale than they had ever been able to do themselves.”

Virtual exhibitions and all sorts of new products – it’s enough to have a look at the annual International Rijksstudio Award to realise the extent and richness of human creativity – are only two of the benefits of open access policies. A greater citizen involvement is another. Cultural heritage is our common property and access to it is not a privilege for the few. Open access is one of the most exciting and beautiful steps towards a more democratic culture, one made and enjoyed by all.

Europeana Virtual Exhibitions webpage

Bio: Maria Vlachou is a Cultural Management and Communications Consultant. She is also a founding member and the executive director of Acesso Cultura | Access Culture, based in Portugal. Her writings may be found on the blog Musing on Culture. Email: mariavlachou.pt@gmail.com