Documenting and Preserving Complex Installation Artworks – Arthur van Mourik (April 2019)

The Centraal Museum Utrecht houses a collection of more than 60,000 objects, including modern and contemporary artworks, and a diverse group of installation artworks.

This post discusses how installation art can be preserved and documented, as well as the practice of making and keeping knowledge and information accessible. Firstly, what is the definition of an installation artwork? Tate defines it as follows: ‘The term installation art is used to describe large-scale, mixed-media constructions, often designed for a specific place or for a temporary period of time.’[1] Museum collections management in general has a long history but the management and documentation of contemporary installation art is more recent (see bibliography). It involves various strategies, and methodologies in order to safeguard the artworks. Plenty of models and guidelines are available but the next step is finding an optimum way of applying conservation methods. In circumstances where money and time are of the essence, it can be difficult to make choices. This post gives a brief overview of some issues relating to installations-management and conservation in the museum setting. The recommendations given here might provide some guidance for your own practice. I always start by asking: what is the artwork that needs to be preserved?

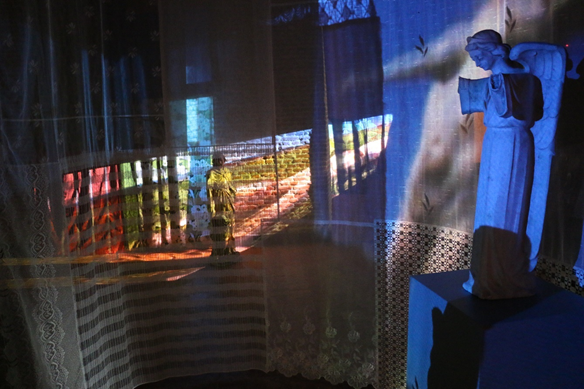

Photo of the exhibition-space where the installation artwork Expecting by the artist Pipilotti Rist ((2011, 2014, 2017), collection Centraal Museum, Utrecht the Netherlands), is being installed. The artwork was on loan for the exhibition Kairos Castle: The Art of the Moment at Gaasbeek Castle, Belgium, 2017. Photo by Arthur van Mourik

After installing the artwork in its final form. Photo by Arthur van Mourik, 2017

Museum practice

When installation artworks are exhibited, it is as if a book is opened and the viewer is able to read the artwork. Before it is installed, the artwork does not exist in its intended form. An installation artwork comes to life when it is installed in an exhibition. The following three artworks were analyzed for research[2].Top Down, Bottom Up by Driessens & Verstappen (2012), is a good example of how to collect and preserve time-based art. This installation artwork consists of four ‘melting-machines’ with heating elements that were mounted vertically to the ceiling of the exhibition space. Purpose-made blocks of beeswax were placed inside the melting machines. Throughout the time of the exhibition, during opening hours, the heating system of a machine was activated. Only one machine at a time was switched on. The machinery would never be operative simultaneously. The heat caused the blocks of the beeswax to melt and drip onto the floor. The re-congealed wax gradually formed a stalagmite. The artwork can be defined as follows: the heating of the wax blocks, the dripping of the wax, its solidification into a stalagmite and its being melted to recreate the wax blocks that are then subjected to the same process once again is a ‘performative’ cycle. The dripping of the wax is an event that can be repeated. The exhibiting of the artwork is thus the ‘performance’ of the dripping. The museum acquired two of these cycles.

Starting point of stalagmite, Centraal Museum 2012. Photo by Arthur van Mourik

Installation view Top Down, Bottom Up, mixed media and beeswax (2012) edition 1 of 4, Driessens & Verstappen, Collection Centraal Museum, Utrecht, Netherlands. Photo by Driessens & Verstappen

This case study gives valuable insight into the administration of artists’ requirements as part of the collection acquisition process. One of the requirements was to reproduce the entire and same process and ‘performative’ cycle, in order to conserve the artwork. The ways to reproduce this cycle was described and administrated in the document ‘installation-instructions’ and was based on interviews with the artist and the former presentation. The definitive document was linked in the object-record of the collection management system for future use. During the working process of the exhibition and acquisition, artist interviews were conducted in combination with project meetings for technical realization. The recorded artist interviews and intensive collaboration were documented and are now accessible via metadata. All these documents can be used for future installations of the artwork. The artist’s intentions have been documented as well as and the definition of the artwork: the process of dripping and recycling. The combination of these two aspects form the definition for preserving and exhibiting the artwork.

Joost Conijn’s Hout Auto (Wood Car), (2001/2002), Collection Centraal Museum, Utrecht, Netherlands. Photo: by Ernst Moritz

Studying the Hout Auto (Wood Car) by Joost Conijn raised issues relating to decision making in conservation and documenting installations in the setting of several multidisciplinary meetings. [3]

In 2001 artist Joost Conijn created Hout Auto (Wood Car) from the base of a Citroën DS, building the chassis from plywood and installing a wood-burning apparatus that powered the engine instead of petrol. In 2002, the artist drove Hout Auto through fifteen European countries, collecting wood along the way and documenting his journey on video. The artwork comprises the car and the video, which is on a DVD. Because the preservation and installation procedures were complex, risky and labor intensive, the Centraal Museum started a research project in 2015 to determine if the vehicle should be kept as a moving car or as an immobile artwork. The Centraal Museum discussed all the outcomes and suggestions with museum professionals (conservators, collections management staff and scientists) and with the technical mechanic of the car during two multi-disciplinary meetings. The research conducted and the exchange of knowledge among these professionals resulted in new insights for the presentation and preservation of the car as a immobile vehicle.

The multimedia installation Expecting by Pipilotti Rist (2011, 2014, 2017) demonstrated that the artist’ participation can be essential and that it is possible to exhibit a site-specific installation in a new form in different locations. The artist participation included; agreeing on modification, designing new installation appearances, providing new improved equipment via a specialized Audio Video supplier and making an assistant available from the artist studio to coordinate installment on location. This assistant was well informed and instructed by the artist, had technical knowledge and could safeguard the intention of the artist during installation.

Installation view Expecting Pipilotti Rist (2011, 2014, 2016) in the convent of Saint Agnes, multi media, Collection Centraal Museum, Utrecht, Netherlands. Photo by Ernst Moritz.

The multimedia installation included video files, a net curtain, computers, mirrors, a sound system, audio files, moving spotlights, textile curtains, light projections and a humidifier with peppermint oil. The installation was primarily made for a specific location in the museum building. After transforming this area in 2012, the site specific and contextual components of the artwork were lost. In order to safeguard the artwork, new plans for its re-installation were discussed. The museum decided to re-install the work in a different space in the Centraal Museum in 2014. Firstly, the artist was contacted to agree on this new form of installation. The artist approved the plans and an agreement was signed. The artist sent an assistant to supervise the installation. After this installation appearance, the artwork was exhibited in a castle in Belgium as part of an exhibition. The artist and her assistant were contacted again and agreed to reinstall the artwork once more. The entire process was repeated in a new space to achieve the artist’s intended ‘look and feel’ of the artwork. The installation was documented by taking photographs and filming the result. New versions of the installation in new locations pointed to the fact that this type of collections management can be more dynamic than just preserving objects conventionally.

Collecting the new

The collections management department is continually working with new installations and therefore constantly faces new challenges. For instance, in 2018 the museum acquired the installation The Black Room (2018) by Robbie Cornelissen, a video installation with projectors, speakers and programmed equipment.

Installation view of The Black Room (2018), Robbie Cornelissen, Collection Centraal Museum, Utrecht, Netherlands. Photo by Ernst Mortiz.

With this piece, a major point was to develop a strategy to preserve the files and the equipment, which might need to be repaired or replaced over time. In addition, artist’s interviews, certificates of authenticity, installation instructions, descriptions of the materials and proper registration of the artwork remain essential.

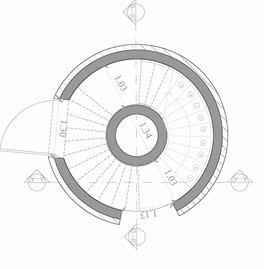

Liquid Garden, 2016, by Tanja Smeets, is another installation in the collection of the Collection Centraal Museum, Utrecht, Netherlands, that is on permanent view. It occupies three floors and parts of it are also attached to the exterior wall of the museum building. At this moment (2018), we are working on a document that holds all the important information in order to re-install the piece. Mapping and measuring the locations with AutoCAD software provides insights for re-installation of the work.

Installation view Liquid Garden (2016), Tanja Smeets, Collection Centraal Museum, Utrecht (NL), laser-cut felt and laser-cut steel, plastic leaf catchers, colored wires. Photo by Ernst Moritz

AutoCAD drawings of the location to give an overview with measurements of installation parts

Recommendations

There is no single solution for coping with all these different kinds of installation artworks, but knowledge, experience, sensitive focus on communication with artists and their assistants, specialized contractors, and technicians are your primary assets. Preserving intangible elements, such as context, performances, time-based art or processes are complex subjects, as are ethical considerations. Securing information and knowledge are keys to unlocking the artworks. As with all exhibitions, project teams are involved in deploying the installation of these complex artworks. Important knowledge and information gained during this process can be documented and used for preservation. How do we apply all of this in practice? Perhaps by following this list of working methods. Try it out. It’s not a solution but might be helpful, so that you start structuring your own best practice.

- Conducting artist interviews and making transcripts

- Creating agreements for purchasing or commissioning artworks

- Documenting working processes: collaborating with experts (technicians, artist’s assistants) transcripts of meetings

- Documenting the artwork in its completed form while on display (video and photographs) for instructions

- Information management: structure documents via metadata based on the collection information system

- Registration of important decision making about the intention of the artwork and other intangible elements (context, process or functionality)

- Conservation of digital components require treatment that can be outsourced

- Procedures concerning installations exhibited by borrowing institutions at different locations are administrated in a loan agreement with supplementary procedures (such as instructions)

- Administering certificates of authenticity and license agreements

Bibliography

– Hummelen, IJsbrand M. C. Sillé, Dionne, Modern Art: Who Cares?: An Interdisciplinary Research Project and an International Symposium on the Conservation of Modern and Contemporary Art, (1999)

– Beerkens, Lydia, The Artist Interview: For Conservation and Presentation of Contemporary Art. Guidelines and Practice, (2004)

– Scholte, Tatja, Wharton, Glenn, Inside Installation: Theory and Practice in the Care of Complex Artworks, (2011)

– Installatie kunst op de kaart (2016 – 2018)

– LIMA in Amsterdam preserves, distributes and researches media art: https://www.li-ma.nl/site/

Bio: Arthur van Mourik is the collections manager of modern and contemporary art at the Centraal Museum Utrecht, the Netherlands. He is responsible for the registration, documentation, conservation and presentation of the modern and contemporary art collection. He can be reached at Amourik[at]centraalmuseum.nl

[2] Mourik, Arthur van, Documenting Three Complex Installation Artworks: Ways of Securing Knowledge and Information for Museum Practice in the Future, paper 26th annual CIDOC – ICOM Conference 2018, Heraklion, Crete, Greece: http://network.icom.museum/cidoc/archive/past-conferences/2018heraklion/. Direct link here.

[3] Rivenc, Rachel and Bek, Reinhard, Keep It Moving? Conserving Kinetic Art, Getty Conservation Institute, Article; The Conservation Ethics of and Strategies for Preserving and Exhibiting an Operational Car: The Motion and Standstill of Joost Conijn’s Hout Auto (Wood Car), by Van Mourik, Arthur (2018)