Encuesta de NEMO sobre el impacto de la situación COVID-19 en los museos de Europa: reflexiones sobre la documentación de las colecciones de los museos – Trilce Navarrete (septiembre de 2020)

The closing of museums due to the pandemic magnified all bottlenecks around the remote access of digital collection documentation, which is at the core of all museum activities, including the provision of services – increasingly online. The pandemic also stimulated greater communication through social media which resulted in the generation of new potential collections, such as the recreation of artworks using household objects or the recording of intangible heritage during the lockdown. What can we say about the future of documentation in museums in this new context?

A brief summary of the NEMO report:

The Network of European Museums (NEMO https://www.ne-mo.org/) launched a survey to document the museums’ response to the pandemic. Nearly 1,000 museums from mostly Europe (48 countries) shared their situation. 62% of respondents were museums with art and history collections, only 30% were located in a rural area, and the majority were small to medium size institutions, with less than 20 staff (80%) and receiving less than 300,000 annual visits (80%).

The lockdown represented a severe test of digital skills and infrastructure to continue work remotely. Video conferencing (used only by 26% of respondents), chatting (used by 17% of respondents), email (used by 12% of respondents), cloud services (used by 11% of respondents), and remote access (used by 10% of respondents) became key tools to enable communication and coordination from home during the pandemic.

Museums were forced to creatively adjust to the new working conditions. The majority of museums (73%) changed staff tasks to accommodate for the lockdown and 32% changed staff’s responsibilities specifically to manage the increased online communication with the public through social media. Though no further explanation was provided about the new tasks of the rest of the staff, we know from other accounts that museums worked on transcription of hand written documents (read with your browser translator here: https://theartofinformationblog.wordpress.com/2020/06/03/collectieprojecten-geimproviseerd-crowdsourcen-in-coronatijd/).

As the lockdown continues, in greater or smaller degree to ensure safety of museum employees and visitors, museums will have to solve the rescheduling of their major events, including openings and the movement of collection objects, as well as the use of resources for documentation of related projects. 50% of museums are expected to discontinue projects and programs.

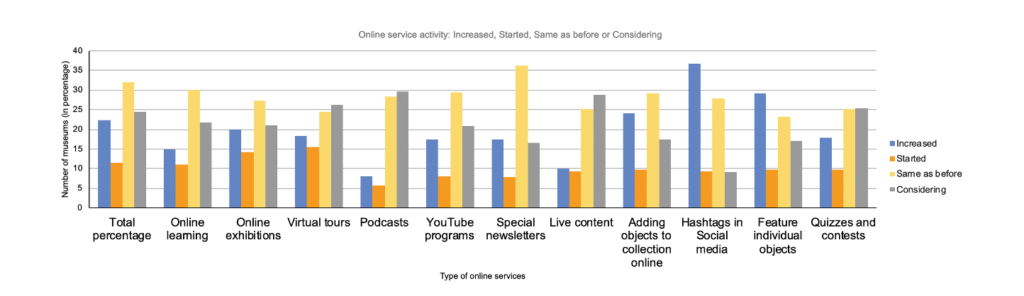

While the lockdown saw a considerable increase in museums’ online communication, including additional virtual tours and video presentations, it is uncertain how much of the gained experience will be adopted in the museums’ new regular activities. It can be expected that some activities will be reduced, such as the massive social media broadcasting that took a toll on staff, or even discontinued. Yet the forced acceleration to adopt digital technology may also result in the adoption and expansion of new ways to better serve the museum community, such as the online tours of exhibitions or presentations of the collections by staff. These activities are directly linked to the documentation of collections, which may gain indirect attention as more objects get featured online. An example is the use of the International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF), which once adopted can ease the use of images for multiple purposes (here is a list of institutions using IIIF and some examples of image reuse: https://iiif.io/community/#participating-institutions).

Figure 1. Online service activity: Increased, Started, Same as before or Considering

Complex projects require an initial significant investment before returns can be seen. Programs such as setting up a public crowdsourcing platform to clean collection documentation (such as the Many Hands Dutch example: https://velehanden.nl/), to collect intangible heritage (such as the Dutch Memory of Amsterdam project: https://geheugenvancentrum.amsterdam/), or to allow reuse by gamers (such as the J. Paul Getty Museum online art generator tool: https://www.polygon.com/2020/4/16/21224318/animal-crossing-new-horizons-getty-museum-art-generator-online-tool) require a strategy and long-term approach to develop. Activities that make use of digital collections to allow for online games (such as Spot the differencehttps://blog.europeana.eu/2020/04/spot-the-differences-8-art-puzzles-to-play/ or Puzzleshttps://blog.europeana.eu/2020/04/museumjigsaw-puzzle-over-beautiful-artworks/ made by Europeana) require technical know-how, otherwise a simpler version can be devised for download (such as the games of the Rijksmuseum: https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/nl/online-rijksmuseum-voor-families/spelen). Incorporating the gained online experience in future projects will require additional organizational adjustments.

Much of museums’ income has been dramatically reduced, since it was generated through the sale of entrance tickets, the restaurant and shop, the rental of spaces for private events, or even government subsidies. Museums in capital cities reported being most affected by loss of tourism (with average weekly losses in the tens of thousands of Euros). As museums have started to open, some additional costs have already emerged, including the redesign of the space to ensure a safe visit (which can be significant, €30,000 for a Dutch museum) or the costs related to digital technology for instance to enable online ticketing –to facilitate the management of visitors at 1.5m distance as required in the Netherlands(https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/actueel/nieuws/2020/06/24/per-1-juli-15-meter-blijft-norm). NEMO has published an interactive map showing re-opening plans (https://www.ne-mo.org/news/article/nemo/an-interactive-map-by-nemo-shows-museum-re-opening-plans.html).

Museums also reported stopping many volunteer programs. In smaller museums, volunteers are responsible for the documentation of collections. The extent to which these small museums can enable the continuation of remote documentation is not known. Reduction of costs by halting free-lance contracts or even laying off staff was most often reported by small to midsize museums. Only a small number of museums (15%) reported considering alternative sources of funding.

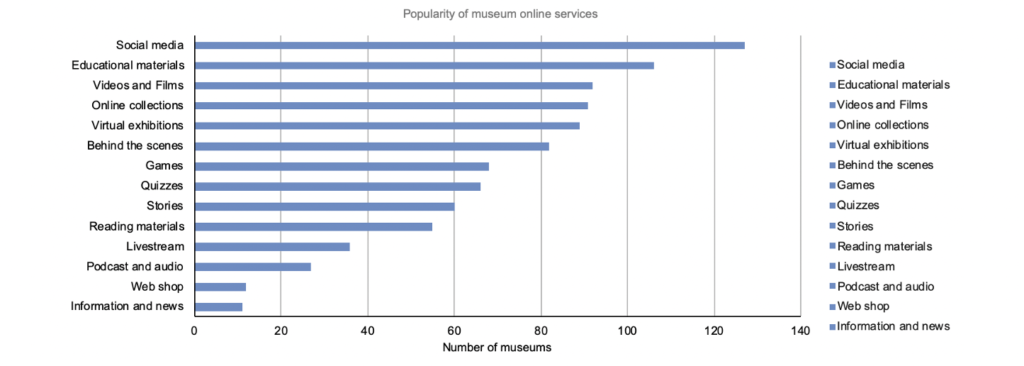

Regarding the response of online museum visitors, the NEMO report shows that the more activities and services museums provide online, the more online visitors they receive. It can be expected that visitors also adjust their museum preferences and that online activities become an increasingly complementary part of a museum visit. Museums are recognized for their collections, their knowledge and their educational role in society, including online.

Figure 2. Popularity of museum online services

Without a harmonized method to measure online ‘visits’ to the varied and complex online presence of museums, it is still difficult to demonstrate the great value of the documentation of museums, including their collections, exhibitions, as well as educational programs. It is easy to imagine that proper documentation will ensure that all the current experience, information, and efforts are incorporated into the knowledge management of the museum for future reuse. Creative approaches to enable this would be welcomed.

The full NEMO report is available at https://www.ne-mo.org/advocacy/our-advocacy-work/museums-during-covid-19.html

Bio: Trilce Navarrete has been the Secretary for CIDOC since 2016. She is a specialist in the economic and historic aspects of digital heritage. She is currently lecturer at the Erasmus University in Rotterdam where she teaches about cultural economics and cultural entrepreneurship and Project Manager at the DEN Foundation for digital heritage, where she supports the development of an observatory for international digital heritage statistics. She tweets @TrilceNavarrete